Transatlantic Racial Protest

“Sister Outsider and Audre Lorde”

Transatlantic Black Queer Sisterhood in the United States and in the Netherlands

Black activism has existed in the Netherlands for much longer than is often assumed. It did not start with the Black Lives Matter protests that we are experiencing today. Instead, the foundations for what would come to be BLM and other modern Black protest movements were already formed in the previous century.

Sister Outsider

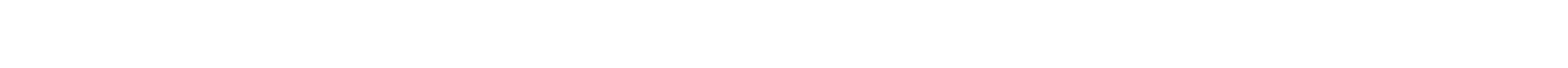

In the year 1983, the Afro-Dutch female protest group Sister Outsider (see photograph) was founded in Amsterdam. Its members, Tania Léon, Gloria Wekker, José Maas and Tieneke Sumter, were impressed and inspired by the life and activism of Afro-Caribbean American author Audre Lorde, a lesbian woman of color who advocated for the visibility of Black Feminism in the United States throughout her literary career. So, they named their collective after one of Lorde’s works entitled Sister Outsider which highlighted the importance of finding common ground with other female outsiders in what Lorde called a predominantly white, heteronormative and patriarchal society.

Image © Romeny, Robertine. “Groep 1984.” Atria: Kennisinstituut Voor Emancipatie En Vrouwengeschiedenis, hdl.handle.net/bibliotheek-archief/collectie/foto/100008482.

Audre Lorde

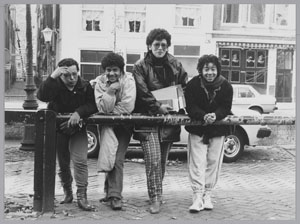

Lorde presented herself as both a ‘Black woman’ and a ‘Black lesbian’. The women of Sister Outsider, who were Black and queer themselves, felt drawn to Lorde’s commitment to making her cause more visible in the United States and wished to do the something similar in the Netherlands. From Lorde, Sister Outsider adopted the concept of intersectionality which has its roots in American Black Feminism. A concept which was already well-used in the United States but had not yet gained much public and academic recognition in the Netherlands. Intersectionality examines the overlap of oppressive systems in society towards women, queer people, people of color, and all of those who are considered to be ‘Others’ (outsiders!) in society. Sister Outsider employed this as a tool to critique racism, sexism and homophobia in the 1980s as well as to create solidarity among Afro-Dutch women. They even invited Audre Lorde to Amsterdam in the hopes to create a lasting ‘Transatlantic Black Queer Sisterhood’, an invitation that Lorde, who was glad to be involved in such an alliance was happy to accept. She visited the group not once, but twice, in 1984 and in 1986.

Images © Kendall, K. “Audre Lorde, 1980, Austin, TX.” Flickr, 1980, www.flickr.com/photos/42401725@N00/2733757260.

Dance Night

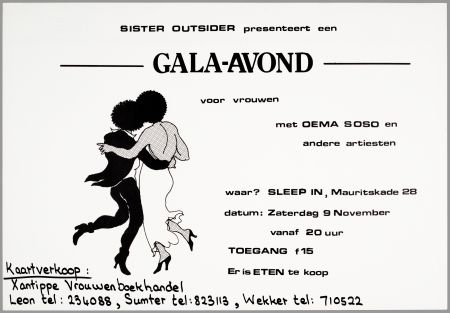

Sister Outsider made it their principle goal to make sure that the struggles of Afro-Dutch women, particularly those who also identified as queer, were made visible through engaging and creative methods that were also largely inspired by Audre Lorde. So, rather than traditional protesting on the streets, Sister Outsider organized events such as literary evenings, poetry reading sessions, and even dance parties, similar to how Audre Lorde did this on the other side of the Atlantic. A poster advertisement of such an event (a Dance Night exclusively for women) can be seen here. This is an example of how Sister Outsider tackled their goal by creating unity rather than division among Dutch and Afro-Dutch women.

Images © Sister Outsider. “Sister Outsider Presenteert Gala-Avond Voor Vrouwen.” Atria: Kennisinstituut Voor Emancipatie En Vrouwengeschiedenis, hdl.handle.net/bibliotheek-archief/collectie/affiche/104000112.

Sister Outsider attempted to bring race, gender and sexuality together in a broader debate on what the common standard of ‘normalcy’ was in the Dutch society of the 1980s. Arguably, their cause is still relevant today. One of Sister Outsider’s former members is Gloria Wekker, who is still a prominent advocate for the cause of Afro-Dutch Feminism and has written several works on the post-colonial legacies on racism and sexism in the Netherlands. Her former membership with Sister Outsider is still visible in the nature of her intersectional approach and in her lifelong cause to make Black and Queer Feminism more visible in academic and public debates on racial identity in the Netherlands, which is a slow but steady process.

If it had not been for Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider might not have existed, which means that intersectionality might have arrived here much later – or not at all. Without their willingness to improve debates about racial identity in the Netherlands back then as a result of Lorde’s legacies in the United States, the Dutch debates on racial and sexual identity today might not have been the same as they are now.