Liberation

Heroes or Criminals?

Looting by American soldiers in Ubbergen during its evacuation in November 1944

Nijmegen and its surrounding municipals were liberated by the Allied soldiers, which consisted of American, Canadian, and British soldiers, during Operation Market Garden in September 1944. What is most distinctly remembered from the liberation, is the enormous sacrifice by those soldiers and the grateful cheering crowds and celebrating civilians. In Ubbergen, a small village near Nijmegen, and many other villages around the city of Nijmegen, this gratefulness was not necessarily appropriate.

Looting

Image

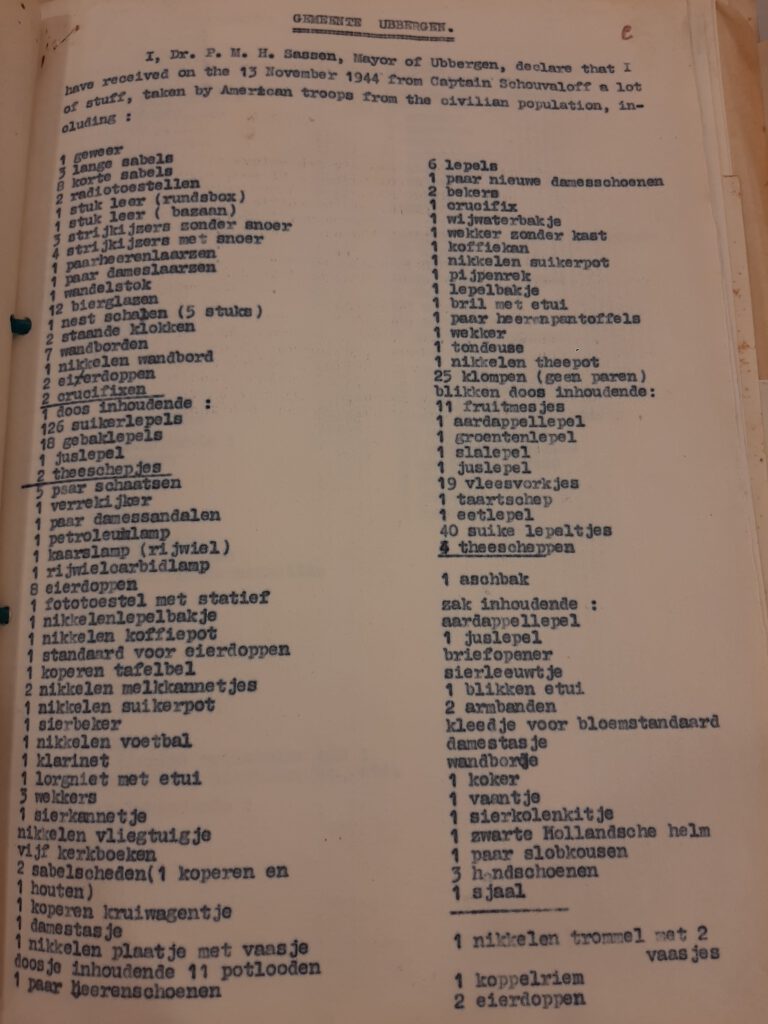

A list with items looted from houses in Ubbergen, confiscated from American soldiers and returned to the Mayor of Ubbergen. Images © Regionaal Archief Nijmegen (RAN), 747 Gemeente Ubbergen 1811 – 1985, inventaris nummer 1451, stukken betreffende aangiften van plunderingen en vernielingen door militairen, 1943-1948. Lijst van goederen.

Textual sources

Peter Romijn, “Liberators and Patriots’: Military Interim Rule and the Politics of Transition in the Netherlands, 1944-1945,” In Seeking Peace in the Wake of War: Europe, 1943-1947, ed. Romijn Peter, Hoffmann Stefan-Ludwig, Kott Sandrine, and Wieviorka Olivier (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2015).

Paul Klinkenberg, Paul Thissen en Paul van der Heijden, Bezet, Bevrijd & Geplunderd: Geallieerde Plunderingen in De Regio Nijmegen, 1944-1945 (Nijmegen: Uitgeverij Vantilt, 2020)

The evacuated areas around Nijmegen were hit hard by the presence of the Allied soldiers. Looting, the act of soldiers plundering goods, took place often. In Ubbergen, Groesbeek, Gennep, and Ottersum, out of the 4757 houses and farms, 4200 (88,29%) were looted from September 1944 until March 1945. What this meant was that houses were broken into and completely emptied. Out of the 1057 houses and farms in Ubbergen, around 900 were looted during the evacuation.

The image of the list gives some insight into what sort of items were looted. When thinking about looting, one might think that the soldiers looted things such as clothes and food, as those were sparse during the war. This did happen, for example, in Ubbergen: American soldiers would shoot cows for food. Other necessary items that soldiers would loot were items to create and support trenches, such as doors and curtains. However, as this list shows, various items that one would not necessarily need in war, such as a clarinet, a woman’s purse, irons, and various decorative items made from nickel and copper, were taken. There are various explanations as to why ‘useless’ items were taken. First of all, many soldiers were looking for souvenirs, such as small windmills, bracelets, and flags, to bring home or to use as lucky charms for protection during the war. Secondly, soldiers looted items that they could sell on the black market or that they could use to pay for the company of ladies. This is the explanation as to why the letter from the mayor of Ubbergen contains expensive items from nickel and copper to women’s items. Thirdly, soldiers would loot for thrill and relief, which is why a lot of liquor was taken and a lot of random items were destroyed. Lastly, in Germany, the soldiers would destroy and loot out of revenge, and take those items back to the area of Nijmegen to sell them.

Memories of the War

Apart from showing what soldiers looted, the letter can be used as evidence that it was American soldiers that looted in the area of Nijmegen. The letter states that these items were confiscated from American soldiers and returned to the mayor of Ubbergen on the 13th of November 1944. The letter does not state whether or not these items were returned to their owners after the evacuation. Adding to this, only American troops were stationed in Ubbergen from the beginning of November until November 11 during its evacuation. This shows that looting was carried out by American soldiers.

As the previous reasons have shown, looting was not (always) necessary, and therefore most of the time a deliberate crime committed by American soldiers. It was difficult to find the responsible soldiers that participated in the looting, as it was not always known which troop was where when. Dutch people were reserved with complaints because they were instructed to be grateful for the freedom that they were granted by those soldiers. Adding to this, General Eisenhower had full administrative authority in the Netherlands from September 1944 until Germany would surrender. This meant that it was difficult to prosecute looters and for citizens to receive damage claims. In contemporary times, the United States is still trying hard to keep up this trend, for example by refusing to join the International Criminal Court, which would be able to prosecute international war crimes.

When looking at the way in which the liberation of Nijmegen is remembered, the phenomenon of looting is rarely mentioned, when in fact nearly every citizen in the area of Nijmegen experienced looting in some way or form. It becomes clear that the remembrance is highly influenced by the heroism of these soldiers, for example throughout the images of soldiers and civilians celebrating together. The reason for this might be how the United States used propaganda in the liberated areas. The United States knew that Dutch civilians might have some resentment against American soldiers, but wanted to shape the postwar peace by bringing propaganda such as magazines, books, and movies. This has obviously been successful, as the looting is not part of the Dutch collective memory of the war.

Textual sources

Peter Romijn, “Liberators and Patriots’: Military Interim Rule and the Politics of Transition in the Netherlands, 1944-1945,” In Seeking Peace in the Wake of War: Europe, 1943-1947, ed. Romijn Peter, Hoffmann Stefan-Ludwig, Kott Sandrine, and Wieviorka Olivier (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2015).

Chile Eboe-Osuji, “All We Want Is Justice for Victims, Says the I.C.C.,” June 18, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/18/opinion/trump-icc.html.

Marja Roholl, “An Invasion of a Different Kind: The U.S. Office of War Information and “The Projection of America” Propaganda in the Netherlands, 1944–1945.” in Politics and Cultures of Liberation.