Liberation

The American Destroyers

vs.

The American Liberators

77 years ago, on the 22nd of February in 1944, the city of Nijmegen was hit by disaster: airplanes flew over the city and dropped their bombs, killing over 800 citizens and destroying a major part of the historic city center. But the bombing of Nijmegen has an even darker side: the city was not bombed by the Germans, but by the American army, an army that was supposed to be its protector and savior. This created a paradox in which the Transatlantic relations between the Netherlands and the United States played a very important role.

Propaganda

After all this time, there is still no real certainty about how such a mistake could have been made. The American side of the story goes as follows: The initial goal of the Allied Air Forces was to bomb the German city of Gotha, which housed the Gothaer Waggonfabrik: a German aircraft factory that had a crucial role in creating warfare products. However, bad weather conditions made it very difficult for the planes to complete their mission. Then the mission commander chose to do something unexpected: he told his men to not abandon the mission completely and that they should hit targets of opportunity instead (other convenient military targets). But due to all the chaos and miscommunication, the bombers were supposedly unaware of that fact that they were then no longer above Germany, and they mistook Nijmegen for a German city and dropped their bombs.

But was this really the truth? Many questions have been left unanswered. For example, the records do not confirm or deny if the pilots knew about their “instructions not to bomb targets of opportunity in occupied countries”. This means that the air forces might well have known that they were dropping their bombs on a city that was located in occupied territory. Nazi Germany used this uncertainty as propaganda and started distributing posters that claimed that the Dutch government had given the Allied forces official permission for the attack on Nijmegen, making it an intentional airstrike. The poster displayed here was created by the Dutch artist Lou Manche, a member of the NSB (Dutch National Socialist Movement), and depicted the bombs that fell from the sky on February 22nd. The text on the poster read: “With friends like these, who needs enemies?”, which hit the right spot, because the Dutch people were already skeptical and distrusting towards the Allies since they were in the Netherlands during Operation Market Garden, and this distrust was increased by the bombardment. However, the campaign never truly took off, because the Americans were welcomed with open arms when the city was liberated. This repression of anger and the willingness to ‘forget’ is an example of the conventional dominant position America within their Transatlantic relationship with the Netherlands.

Image

German propaganda created for the citizens of Nijmegen, Enschede, and Arnhem. Images © Regionaal Archief Nijmegen (RAN). Collectie Tweede Wereldoorlog Nijmegen 1932-2014, inventarisnummer 3000.188. German condemnation of the bombings on Nijmegen, Arnhem, and Enschede in 1944: “Van je vrienden moet je ‘t hebben”.” 25.2.1944 – 20.3.1944

Textual sources

Joris A. C. Van Esch, “Restrained Policy and Careless Execution: Allied Strategic Bombing on the Netherlands in the Second World War,” War & Society 31, no. 3 (2012).

“Bombardement van Nijmegen” Andere Tijden, NPO 1, January 20, 2004.

Anger

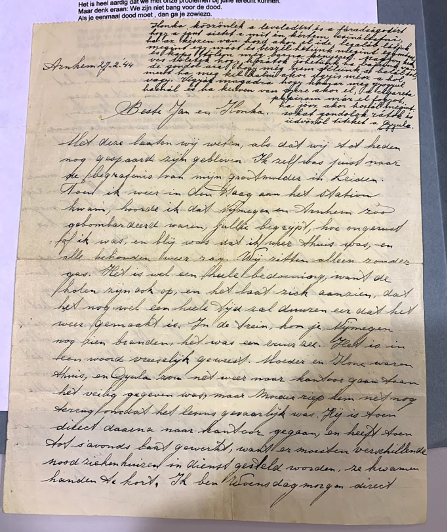

Nevertheless, there are still several sources that show the anger and sense of betrayal that lived among the citizens after the bombardment. A fitting example can be seen in the images above: a letter written by Rie, a Dutch woman living in Arnhem during the war, that describes what happened on February 22nd, 1944. In the light of the Dutch sentiments towards the Americans, Rie says something striking: “If this is the way in which they want to liberate us they better stay away, because these people are no liberators, they are murderers.” This illustrates that the resentment towards the U.S. army was, in fact, present among the people of Nijmegen and surrounding areas – there were clear tensions within the Transatlantic relation between America and Nijmegen at that point.

Still, the American preeminence seemed to prevail. This is also presented in the fact that the Dutch government never really demanded a thorough research into what had happened and how they could have made such a mistake. Due to several reasons, the Dutch government and Queen Wilhelmina were not fully informed about the bombing for a long time. According to them this was the reason that they decided against any actions towards the United States: they claimed that they did not have enough facts to confront the Americans. Even if they had known, actions would probably not have been taken, because the Dutch government was known to be accommodating towards America and tried to avoid any confrontations. This was also represented within the role of General Eisenhower, who through a legal agreement received full authority over administrative matters in the Netherlands after it was liberated. Even now, 77 years later, the Netherlands has never confronted the Americans about the bombing again.

Image

Original Dutch source text: “Als ze ons zo komen bevrijden, dan kunnen ze beter wegblijven, want dat zijn geen bevrijders, dat zijn moordenaars.” Images © RAN. 579 Collectie Tweede Wereldoorlog Nijmegen 1931-2019, inventarisnummer 712. Rie. Letter concerning the Bombing of Nijmegen to Jan and Ilonka. Arnhem, February 27, 1944.

Textual sources

Joris A. C. Van Esch, “The Nijmegen Bombardment on February 22, 1944: A Faux Pas or the Price of Liberation?” (London: Middlesex University, 2010).

Peter Romijn, “Liberators and Patriots: Military Interim Rule and the Politics of Transition in the Netherlands, 1944-1945,” In Seeking Peace in the Wake of War: Europe, 1943-1947, (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2015).

A Mistake?

In of all of this uncertainty and ambiguity we see the immense influence that America has had in the relationship between the United States and The Netherlands. Because of its dominant character, a lot of questions that should have been asked after the bombing, were mostly left unanswered. This kept America in the role of a savior, a liberator, and a friend to the Dutch people. Today, the disastrous event is still known as the vergissingsbombardement: the bombardment that was a mere mistake. But is that fair assessment or not? That’s up to you.