Americanization

Valentine's day and the americanization of germany after World war ii

Thanksgiving dinners, Super Bowl parties, gender reveals – many American holidays and celebrations have crossed the Atlantic Ocean in recent years. While some Europeans are excited about participating in these new traditions, others complain that European culture is becoming too “Americanized.” However, the import of American customs is not a new phenomenon: Holidays such as Mother’s Day or Halloween, which are now well-established in many European countries, originated in the United States.

Valentine's Day: An American Import?

Image

Advertisement for Valentine’s Day cards by L. Prang & Co., 1883. © L. Prang & Co. Prang’s Valentine Cards. 1883. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Prang%27s_Valentine_Cards2.jpg

Sources

Schmidt, Leigh Eric. “The Fashioning of a Modern Holiday: St. Valentine’s Day, 1840- 1870.” Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 28, no. 4, 1993, pp. 209–245.

How do American products and practices make their way across the Atlantic? Do these cultural imports influence European culture, or the other way around? And how “American” is American culture really? The emergence of Valentine’s Day in West Germany after World War II offers a fascinating glimpse into post-war Americanization.

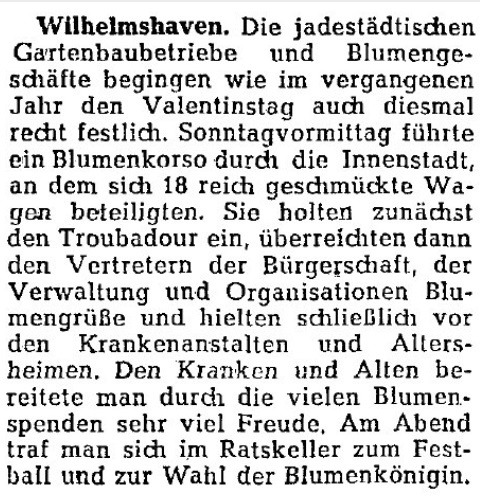

Valentine’s Day as a celebration of love and romance was not an American invention. February 14, a saint’s day dedicated to two medieval martyrs both named Valentine, was first associated with romantic themes in the works of English poet Geoffrey Chaucer and his literary contemporaries. Their poetry played an important role in transforming St. Valentine into a patron of lovers and February 14 into a day of romantic folk customs in Great Britain.

In the 1840s, Valentine’s Day celebrations started to become popular in the United States, where the emergent consumer culture quickly gave the holiday a distinctly American tinge. American manufacturers, such as the Massachusetts-based L. Prang & Co., began mass-producing and advertising the popular Valentine’s Day cards, and other kinds of material gifts soon followed. Valentine’s Day grew to become one of the most popular holidays in the United States.

It was this heavily commercialized version of Valentine’s Day that ultimately arrived in Germany after World War II, demonstrating that American culture is often more European than it appears. Despite the romantic holiday’s British roots, its transformation through American consumerism and its cultural significance in the United States contributed to Valentine’s Day’s association with American influences in Germany.

Soldiers and florists

Images

Top: © Magnussen, Friedrich. Schaufenster zum Valentinstag. 1969. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Schaufenster_zum_Valentinstag_(Kiel_44.388).jpg. Bottom: © “Laßt Blumen sprechen am Valentinstag!“ Passauer Neue Presse (13 Feb. 1959) p. 7.

Sources

Matthew Hilton. “Consumers and the State since the Second World War.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 611, 2007, pp. 66–81.

Alexander Stephan ed. “A Special German Case of Cultural Americanization.” The Americanization of Europe: Culture, Diplomacy, and Anti-Americanism after 1945, Berghahn Books, 2008, pp. 69–88.

American soldiers stationed in West Germany after World War II frequently functioned as cultural ambassadors of a sort, and they likely played a leading role in introducing Valentine’s Day to the German public. The holiday first emerged in the south of the country, most of which was part of the American occupation zone. Considering the romantic nature of the celebration and the common fraternization between soldiers and German women, it is probable that these contacts contributed to the increasing popularity of Valentine’s Day. The establishment of a new holiday centered around material gifts, however, can also be viewed as the result of a more indirect American influence: the spread of American consumerism in postwar Germany. Combined with the financial aid provided by the Marshall Plan and the willingness of the strengthened German economy to absorb cultural imports of all kinds, the groundwork was set for the establishment of a consumption-based holiday.

Not all agents of Americanization are of American origin, however. The German floral industry played a vital role in promoting the holiday as an occasion for purchasing flowers for loved ones. One 1959 article from the Bavarian newspaper Passauer Neue Presse titled “Laßt Blumen sprechen am Valentinstag!” emphasizes the involvement of the floral industry and several florist associations and committees. The article portrays Valentine’s Day as a positive enrichment of German culture while highlighting its cultural significance in the United States.

Valentine's day in the German press

After World War II and the fall of the Third Reich, Germany broke with its previous national identity and was primed for cultural influences from abroad. The rapid spread of Valentine’s Day as a new holiday tradition illustrates the general openness for new cultural practices. Newspaper articles from the 1950s and 1960s reveal insights into the early celebrations of Valentine’s Day and some reactions from the German public.

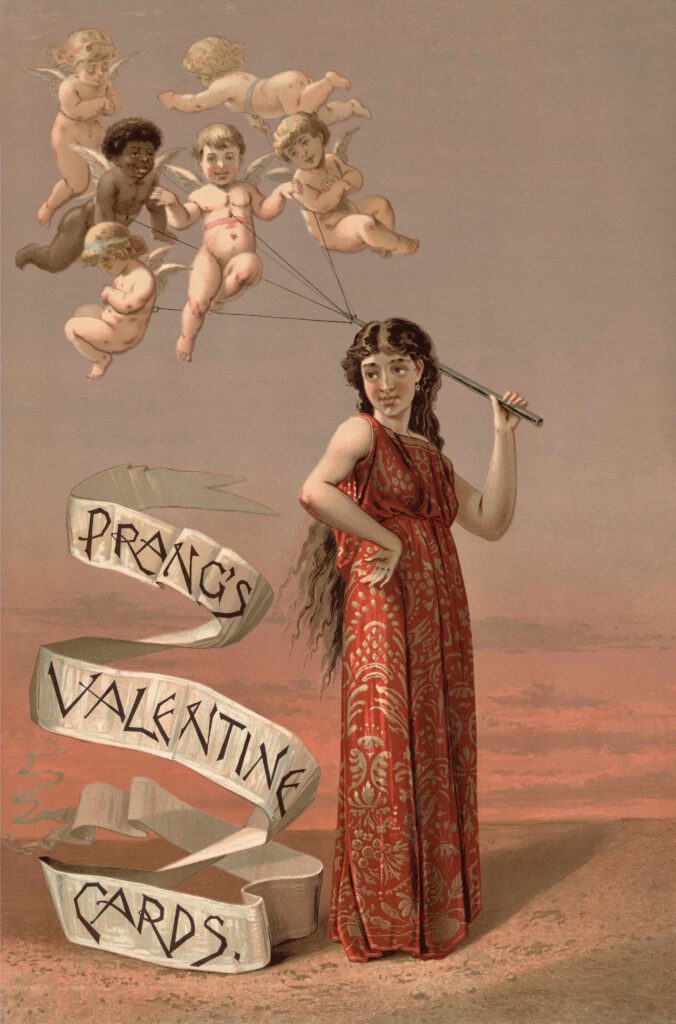

While the floral industry had adapted the holiday to its own commercial needs, there were also some local attempts at giving Valentine’s Day a more German feel. In the northern city of Wilhelmshaven, Valentine’s Day was celebrated in 1955 with a motorcade of vehicles decorated with flowers. In the evening, a Valentine’s Ball was held that included a vote for a “flower queen.” These public celebrations – as opposed to private gift exchanges – resemble already established German traditions such as Karneval and Schützenfest.

Some Germans, particularly voices from the conservative and intellectual elite, were more skeptical towards the cultural value of Valentine’s Day and other American influences. In an op-ed from 1956 titled “Nelken für Valentin,” one columnist belittles the impact of the United States on German culture by reducing these influences to the most trivial cultural imports, such as chewing gum. Other columnists frequently criticized the materialistic and commercial focus of the holiday.

They were not always wrong – as a newspaper from 1964 shows, reports about Valentine’s Day in the Sixties were often accompanied by an ever-growing number of ads for local florists. Many of them were affiliated with Fleurop, a flower delivery network that had merged with American and British partners shortly after the war to found the international company Interflora Inc. The history of Valentine’s Day therefore not only offers insights into processes of Americanization, but also a glimpse into the beginnings of postwar globalization.

Images

Top: © “Blumen für die Kranken.” Jeverland-Bote (15 Feb. 1955) p. 3. Middle: © F. Müller. “Nelken für Valentin.“ Passauer Neue Presse (14 Feb. 1956) p. 5. Bottom: © “Zum Valentinstag am 14. Februar.” Der Gemeinnützige (13 Feb. 1964) p. 3.

Sources

“Fleurop – History.” Fleurop, www.fleurop.ch/en/s/fleurop–history.

Stephan, “A Special German Case.”